POVERTY MATTERS

Poverty is created. Poverty is neither inherent in nor a product of nature since by its nature, poverty is an unnatural state imposed upon the powerless. Humans have created engines for extracting vast amounts of wealth from nature, using the economic power of that largesse to exploit, subjugate and marginalize the majority of the world’s population in effect keeping them in a chronic state of poverty.

How much of the global population? A recent post on Fast Company by Jason Hickle, Martin Kirk and Joe Brewer puts it this way:

For a start, it all rests on The World Bank’s $1.25-a-day poverty line, which is insultingly low. The UN body UNCTAD has pointed out that anyone living on less than $5 a day is unable to achieve “a standard of living adequate for health and wellbeing”: the inalienable right enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. If you use that figure, a soul-scorching 5.1 billion people, or 80% of humanity, are living in those conditions today…The recognition that the only way for a tiny group of people to become obscenely rich is for huge masses of others to be kept chronically poor.

Even the mass media, so full of stories extolling the elegant lifestyles of the elites, while lamenting the tribulations of the underclass tradespeople and domestics a la Downton Abbey, reinforce this myth of noblesse oblige being a fount of reason and a cornucopia of good intentions for solutions to world hunger – as if the poor need the permission of the rich to eat or even survive, when in reality, it is these elites and the economic rules they dictate that creates poverty. Time to change those rules.

HISTORY MATTERS

We are a nation of immigrants – even the indigenous societies that thrived on the North American continent before the invasive European culture all but wiped them out came from somewhere else. Our story then is a tale told by immigrants. Here is one such tale.

Anna and Ivan emigrated to this country a little more than a century ago, amid a trans-generational and pan-cultural diaspora that emanated largely from Central and Eastern Europe, Russia, and the Middle East, which was precipitated by a revolt of the ethnic underclasses against the ruling monarchies and dynasties of the 19th Century, an upheaval that would ultimately lead to The Great War and result in the deaths of tens of millions of the underclass, including Slavs and the lumpen conscripted to actually fight it.

Anna took the more conventional route, boarding the S.S. König Albert in Bremerhaven for the week-long voyage across the Atlantic in steerage. Ivan took a more adventurous path, moving to Italy for a time and then on to France where he got a berth on a freighter bound for Tampa Bay, Florida. Soon after his arrival there, he “jumped ship” – leaving his job and effectively severing all ties with Europe and his homeland Galicia, which was then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Ivan and Anna met for the first time in New York City – even though their families had lived within a few kilometers from each other back in Galicia separated by the River Strypa – and were soon married in NYC during May of 1916 at a local Greek Orthodox Church.

From New York City they began a nomadic trek across the Northeastern U.S., hiring on as migrant farm workers where and when they could find the jobs and shelter, winding up for a time in Cleveland before ultimately moving North to Michigan where they settled in the Thumb District.

They were of the peasant class who worked the Earth, dirt poor immigrants who didn’t speak English — at least not very well. Everybody had to work, even the children. Because Ivan was a “wetback” — technically an illegal alien — the family kept their heads down, didn’t speak to anyone, labored as hard as they could and as “foreigners” tried not to raise the suspicions of the conservative country folk they worked for.

There was no welfare – not that they would even have been able to get it. There was no healthcare. If you got sick, there was the local GP but you had to pay or barter for medicines such as there were. Then there was the Depression. They moved often from one tenancy to the next, once three times in one day. At final count they lived in or worked on more than 20 different farms in 25 years until finally being able to afford a small house with a white picket fence on Main Street [actually Howard Street] across from the bank in Croswell.

Yet they raised four kids; two boys who went off to fight heroically in WWII; and two girls – one who became a banker and the other ran her own hair salon; children whom had families of their own producing ten grandchildren, and more than score of great-grandchildren.

There was a great celebration when Anna finally received her official naturalization papers in 1945 – 32 years after she first stepped across the portal at Ellis Island.

Ivan had to wait until 1947 for his but lived only three more years when he was diagnosed with terminal cancer. Since there was no Medicare, and he was unable to pay for surgery and the subsequent therapy even after selling off his beloved Ford tractor, he suffered in constant pain until at the age of 58 he took his own life.

The extended family grew. The grandchildren and great-grandchildren all became great consumers under the economic caste system that citizens of the world have become dependent upon, succumbing to the mandate to be the pliable good citizens necessary for such systems to flourish and even to survive.

HAPPINESS IS AN EMPTY WALLET

There is then this symbiotic co-dependency between such an economic system and we, its consumer subjects. In order for the former to continue to function, the latter must stay lashed to the wheel and consume so that the system self-perpetuates. If consumer behavior patterns are altered, either by choice, by happenstance, or more than likely mandated by changes in economic policy, this cycle of production-for-consumption can become less efficient, forcing the casino-mentality of both the banking sector that funds it all, built largely upon highly leveraged speculation over the projected cash flows emanating from consumers, and the corporate entities with their well-insulated senior management that roll the dice, altering their market strategies by either cutting costs in order to produce a cheaper and by inference more profitable product or by consolidating industry positions through merger and acquisition or both.

That’s why if you read any business cash flow projection (if you can break into a Board Room and steal one) for a publicly-traded business, there will always be a targeted increase in year over year revenue flows. Why? The expectation of growth affects stock prices which are essentially bets on future dividends – meaning fee and interest income for brokers and lenders, stock options and carried interest for senior management and a taste left over for the shareholder. Revenues are always inflated while operating costs must be minimized.

But don’t actual stock market results have more of an effect on share prices, you ask? Of course, but the stock market is a casino plain and simple. So for every leveraged-to-the-hilt loser there is at least one winner and the house – the bank – dictates the odds, takes its cut, and controls the outcome.

The inherent flaw in such a system and in reality its Achilles Heel is that its target, the ever-loyal consumer is also its greatest risk. Too much consumption creates too much debt which results in default. Too many defaults create a recession. Recessions are bad for business but good for elites because they get to gobble up the assets of distressed businesses and non-performing properties at bargain-basement prices. Recessions are an integral part of a plutocracy. They are the mechanism for how the elites consolidate power.

If this economic engine of inconspicuous consumption stalls out, constricting the cash flow Wall Street gamblers need for creating interest and fee income from bets on future output, then this whole Ponzi Scheme called The Free Market starts to cost the plutocracy that benefits from its neoliberal policies more than it is worth — and the owners do not want that to happen.

How do these owners prevent this from happening? One methodology – let’s categorize it as a macro-social construct (a loosely-related metaphor for Ferdinand Tonnies’ Gesellschaft concept of society) – is to implement political strategies that promote the Four D’s of economic assimilation: the destabilization of an economy, the destruction of its public safety net, the enforced deprivation of the middle and lower classes, culminating in complete dependency on privatized services – and to do this in perpetuity – aimed at entirely eliminating any competing socio-economic entities and their constituents. Everybody is an enemy until they are commodified into paying customers .

Another tactic – we can term it micro-social in scope since it is targeted more toward groups of individuals or a community – is accomplished through the branding of Happiness. The average citizen is bombarded by mass media propaganda campaigns, targeting them both directly and subliminally literally hundreds of instances each day, extolling the twin virtues of demonstrating good citizenship and of being fulfilled through the very act of consumption by simply emptying one’s wallet.

What is the basis for these micro and macro-social programs? Economic power. What are its goals? Domination and control. What is the nature of these campaigns? Class warfare. What is this strategy called? The Forever War. How is it then implemented? By disseminating and imposing the economies of power through a privatized international banking system solely created for and controlled by the owners of capital. Here is how it works.

ECONOMIES OF SCALE

The Money Supply

First some background. Central banking systems were created to perform a dual role. As the monetary authority for a given country, they are tasked to plan and manage economic programs that both shape the financial health and well-being of their constituent member banks and ensure the financial stability of the economy that these banks themselves function in. The tool that these central banking authorities employ to implement such plans is called Monetary Policy – basically the control of the money supply. To expand the supply of money, a central bank could opt to print more money or to reduce interest rates – which makes existing money cheaper – or in some combination of the two, do both. To contract the money supply – a strategy we have come to know as “austerity” – an opposite monetary policy would pertain making money harder to get and by inference more expensive.

Quantitative Easing

There is a third option open to central banks for stimulating the economy, deployed when standard monetary policy has become ineffective – meaning short-term interest rates have approached or reached zero and cannot be adjusted any lower in order to effectively increase the money supply. It is called Quantitative Easing (QE).

A central bank enacts quantitative easing by purchasing—without reference to the interest rate — a set quantity of bonds or other financial assets on financial markets from private financial institutions. The goal of this policy is to facilitate an expansion of private bank lending; if private banks increase lending, it would increase the money supply. Additionally, if the central bank also purchases financial instruments that are riskier than government bonds, it can also lower the interest yield of those assets. —- Wiki.

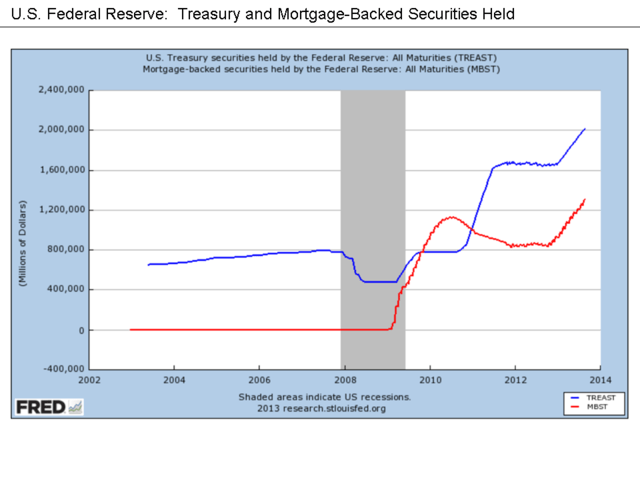

The effectiveness of QE strategies is hotly debated. On the one hand, as in the case of the ongoing QE1, QE2, and QE3 programs conducted by The Fed since the 2008 Great Recession, QE has been credited by some to have propped up the balance sheets of the banks making them appear more solvent; kept interest rates low resulting cheap money for debtors and stimulated large asset purchases; led to a surge in stock prices as investors moved their money from low yield bonds; taken risky or even toxic bonds and mortgage securities off the market while the housing market rebounds; and contributed to increased consumer confidence and consumption.

Critics however, argue that QE has led to increased income inequality since most of the cash generated from such programs adhere to investors in the form of profits or are used by banks to either invest in emerging markets, commodities, and to speculate in highly profitable derivatives or to lend out to its corporate clients at low rates who in turn use the cheap money to buy back some of their outstanding shares, which in turn inflates their stock values, thereby creating conditions conducive for another global meltdown. Other criticisms have centered on charges that QE is just “printing money” which has the effect of monetizing debt — or financing the government’s deficit. As a point of reference, as of the end of 2014, the Fed held $4.5 Trillion in such “assets” it had taken off the market.

Leverage

In a recent post on her blog Web of Debt titled “How America Became an Oligarchy”, attorney and founder of the Public Banking Institute Ellen Brown traces the rise of the international private banking industry and how it has controlled political fortunes and ultimately turned democracy into oligarchy by controlling the money supply. Citing theologian and environmentalist Dr. John Cobb’s recent paper titled “The Collapse of Democratic Nation States”, Brown excerpts the following quote:

The influence of money was greatly enhanced by the emergence of private banking. The banks are able to create money and so to lend amounts far in excess of their actual reserves. This control of money-creation … has given banks overwhelming control over human affairs. In the United States, Wall Street makes most of the truly important decisions that are directly attributed to Washington.

The vast majority of the money supply in North America and Europe is created by private bankers – 97% according to PositveMoney.org. In the US, functional control of the currency rests with the Federal Reserve which doles out money to its privately-held member banks at “low or no” interest rates, but titular control of the money supply rests with the Department of The Treasury whose head, the Secretary of The Treasury is a political appointee.

The Treasury actually prints the money through the Bureau of Printing and Engraving and its system of mints, then “sells” paper currency to the Federal Reserve at cost and the coins at face value (even though in some cases they cost more than face value to mint). More on this process later. But the bulk of the money supply is neither created from nor backed by specie but by paper in the form of government or corporate bonds, loan contracts, stocks, and lines of credit created by private bankers.

How do these privately-owned banks create money? By giving out credit lines to businesses, mortgages to prospective “homeowners”, and loans to other banks in exchange for debt – a contractual promise to pay off the loan plus interest over a given time period or term. These banks can then potentially “grow” the money supply by enormous amounts limited only by statutetory restrictions on funds they must keep on their Balance Sheets as a Reserve against potential defaults.

Fractional Reserves

For example, during lean times this fractional reserve requirement might limit a bank’s loan to reserve or liquidity ratio to 10%. This means the bank would have to keep as a reserve – on deposit with its district Federal Reserve branch – a minimum of 10 percent of its outstanding customer deposits or liabilities, so theoretically it could loan out $10 for every $1 in reserves. During flush times like before the 2007 banking collapse, this liquidity ratio had ballooned in some cases to 80:1. That meant certain highly-leveraged banks had loaned out $80 for every $1 in reserves and were also collecting interest at market rates on the $79 differential on top of the fees they collected for funding the loans in the first place.

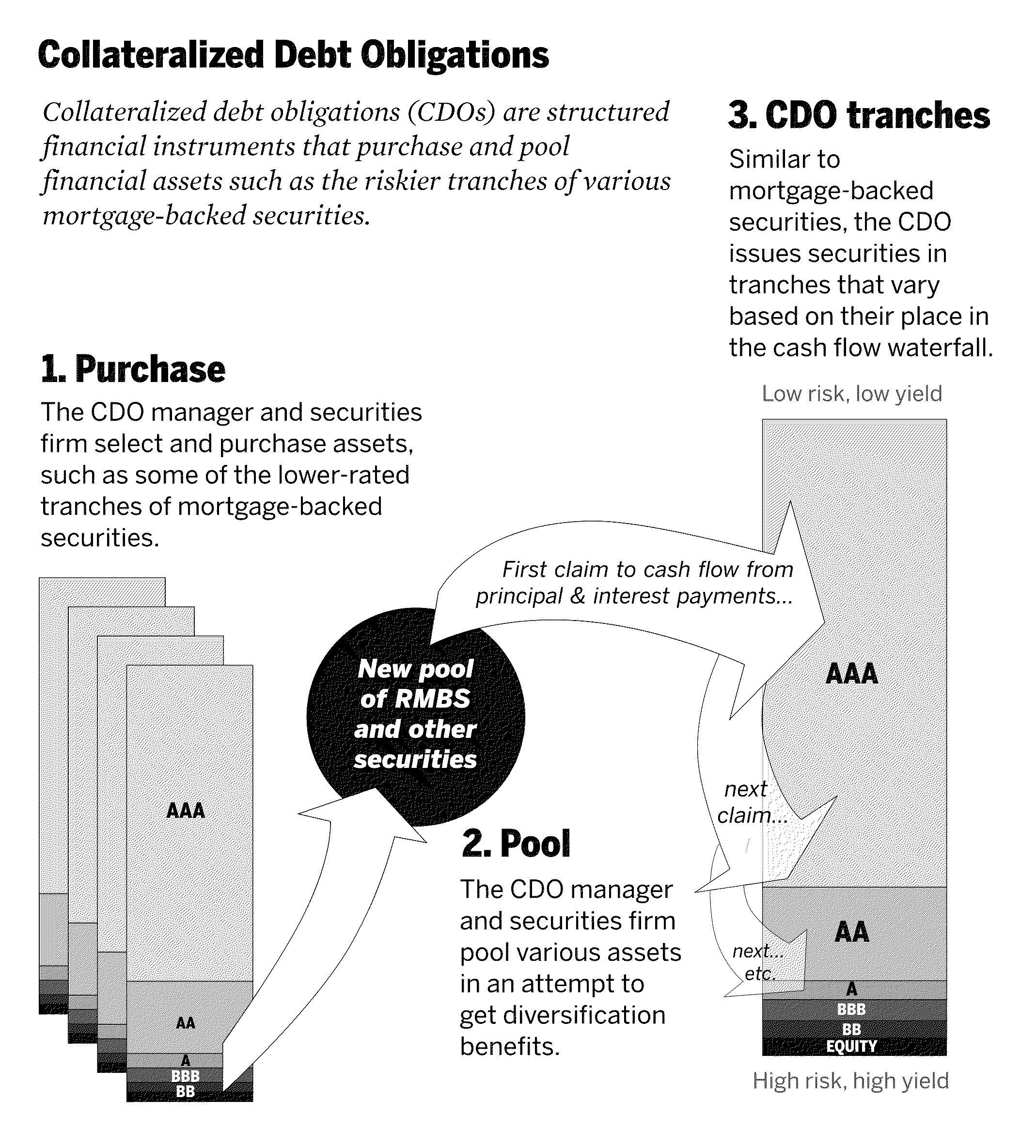

Based upon the projected cash flow from just such an income stream, a lender bank could aggregate or package these loans as securities, often called collateralized debt obligations or CDOs (since 2008 re-branded as Bespoke Tranche Opportunities), and after first making sure to receive the blessings of the ratings agencies such as Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s, sell them to insurance companies, pension funds, municipalities or even banks in foreign countries like Iceland, Ireland, Greece, and Spain who would in turn further leverage the potential income stream from these CDOs to finance additional consumer lending programs, to fund home mortgages, create bond issues for capital improvements, engage in international trade balance of payments transactions, or to buy additional securities on the stock markets.

So you can see that the original $79, potentially being leveraged many times over with this “multiplier effect”, could cause both the money supply to expand significantly and also create the risk of a burgeoning mountain of debt that would have to be paid at some point in the future.

Derivatives

In order to insulate themselves from market fluctuations and potential default, the lender banks would take out insurance policies – derivatives with exotic names like Credit Default Swaps (CDS) or Capital Relief Trades underwritten by other financial institutions including investment banks, hedge funds, and insurance companies.

In a post from 2008 titled It’s The Derivatives Stupid! on her Web of Debt blog, Ellen Brown explains what a derivative is:

“Derivatives are financial instruments that have no intrinsic value but derive their value from something else. Basically, they are just bets. You can “hedge your bet” that something you own will go up by placing a side bet that it will go down.”

So how does the most common form of credit derivative, the Credit Default Swap (CDS) work? A CDS is a bet between two parties on whether or not a given company will default on its credit obligations — typically a contract or a bond. Ellen Brown illuminates further:

“In a typical default swap, the “protection buyer” gets a large payoff from the “protection seller” if the company defaults within a certain period of time, while the “protection seller” collects periodic payments from the “protection buyer” for assuming the risk of default. CDS thus resemble insurance policies, but there is no requirement to actually hold any asset or suffer any loss, so CDS are widely used just to increase profits by gambling on market changes…. In one blogger’s example, a hedge fund could sit back and collect $320,000 a year in premiums just for selling “protection” on a risky BBB junk bond. The premiums are “free” money – free until the bond actually goes into default, when the hedge fund could be on the hook for $100 million in claims.”

This is how banks and investors ostensibly manage risk. The underwriters themselves might subsequently aggregate these risk management swaps or even create new ones, whose relative value to potential investors is derived solely from the future expectations on the market value of the original underlying CDOs they were created as insurance for in the first place (hence the name “derivatives”), and sell them as well to similar institutional customers even further expanding portfolios of assets with little or no actual value other than from expectations, and also exponentially multiplying the potential for loss.

Next – most likely immediately post-sale – the underwriters might earmark a portion of the proceeds of such a swaps transaction, (which to be clear, amounts to issuing an insurance policy with a cash value equal to the agreed upon notional value of the package of swaps (the CDO) being insured, in exchange for a transaction fee and an either fixed or variable periodic “premium” to be paid by the insuree), in order to purchase futures contracts that allow the underwriter the option to claim the right to buy back or “short” these futures, at pre-determined prices levels, along with certain “stop points” if expectations rise – essentially placing a bet that the future value of the original securities (CDO) would fluctuate up or down over a given period and if so, serve as a hedge against the whole deal going South.

Because the derivatives marketplace, unlike that of the insurance industry, is completely opaque to regulation, the underwriting agency might then be able to create multiple CDS agreements that each cover all or a portion of the same CDO tranche, and market them to any third party investor willing to bet against the potential change in value of the underlying “assets” of the CDO.

An Example

So for instance, if the original package of CDOs had a “notional” (face) value of $100K, our underwriting agency could issue additional swaps “policies” (CDS), to as many completely independent investors as are willing, whom have no other stake in the transaction other than speculative, each CDS contract having the same face value of $100K. For the sake of our example we’ll use four. As long as the original institutional customers keep their monthly premiums current on the original swaps contract with our underwriter and the CDO portfolio keeps producing the expected income stream, everything is gravy for both the institutional investors and the underwriter who is collecting monthly premiums on both the original CDS and the secondary CDS contracts held by our four unrelated investors.

Our four speculators (we’ll call them hedge funders) however, who are really betting that the whole deal will wind up in the shit can, might individually or in collusion take out contrary futures positions on the original CDO tranche or even on the potential cash flow of the original institutional customers, in an attempt to negatively influence market expectations or credit ratings, and drive down the ability of the institution to generate enough income to operate. Plus, depending on their expectations about future market interest rates, our hedge funders might go to back to these institutional customers and offer to engage in an interest rate swaps deal.

Interest rate swaps transactions are based upon relative expectations about fluctuations in future market interest rates. They typically involve two parties, with an intermediary fiduciary serving as a clearinghouse, who agree to swap income streams based on assets (but not the assets themselves) having the same “notional” value, for a contractual period of time; one income stream whose payments terms specify a fixed rate of return to be exchanged for another that has a variable rate coupon.

Thus our hedge funders might believe that future interest rates will trend downward for a time, hence be tempted to offer our institutional customers an income stream from one or more bond portfolios with a variable coupon rate in exchange for that from the CDO which might be based on a fixed rate. If the hedge funders are right, they will profit and the institutional customers will lose money on the swaps deal – potentially having the desired negative effect on value of the investor-held portfolios or operations (at least for the term of the swaps), possibly triggering a default on the CDS contract with the underwriter and subsequently force the underwriter to fork over the cash value of the swaps contract ($400K). If they’re wrong, the hedge funders will be out the income stream differential on the interest rate swaps contract plus they are still making payments on the CDS contract they bought into from the underwriter.

This illustrates the power of leverage. In our example, the underwriter has multiplied both its $100K liability and its income from the CDS contracts four times, solely based upon expectations. If the expectations prove out, it will enjoy a profit. But leverage can work both ways both here and in the real world, resulting in an explosion of potential debt that far exceeds the value of any underlying assets making such overextended wagers extremely vulnerable to speculative pressures from potential competitors.

Gamesmanship

Here is a real-world example of how risky leverage can be. In a post from 2012, Web of Debt posted an article referencing a report from Rudy Avizius of the Market Oracle U.K. about a then major global financial derivatives broker called MF Global that was forced into bankruptcy because of more than $6 Billion in losses on highly leveraged repurchase agreements based on the bonds of several European nations including Greece. Avizius writes:

[A]n agreement was reached in Europe that investors would have to take a write-down of 50% on Greek Bond debt. Now MF Global was leveraged anywhere from 40 to 1, to 80 to 1 depending on whose figures you believe. Let’s assume that MF Global was leveraged 40 to 1, this means that they could not even absorb a small 3% loss, so when the “haircut” of 50% was agreed to, MF Global was finished. It tried to stem its losses by criminally dipping into segregated client accounts, and we all know how that ended with clients losing their money. . . .

However, MF Global thought that they had risk-free speculation because they had bought these CDS (Credit Default Swaps) from these big banks to protect themselves in case their bets on European Debt went bad. MF Global should have been protected by its CDS, but since the ISDA would not declare the Greek “credit event” to be a default, MF Global could not cover its losses, causing its collapse.

So who is the ISDA? Well it is the International Swaps and Derivatives Association consisting of more than 800 members who themselves are derivatives dealers, banks, insurance companies, and something called “end users”. More than often these are the very entities that underwrite derivatives contracts like CDS. So if a client’s bets go South, the affected ISDA member – a bank who issued the CDS to cover these bets – has fork over the cash value of the insurance.

However, in the case of the ill fated MF Global, the house decided there was no default, in effect ruling that one of its Club members didn’t have to pay the insurance it owed on the CDS to MF Global, forcing the firm out of business – a classic case of “we don’t like the game, so we’ll take the our ball and go home”.

The Grexit

Greece was seemingly in the financial spotlight every week as analysts wring their hands over possible default on the EuroBonds the country has been saddled with coupled with the very real possibility of Greece’s exit from the EEU and the potential global economic fallout from such a happenstance.

Goldman Sachs has had its tentacles wrapped around Greece for almost a decade coercing the government to accept opaque derivatives contracts in exchange for loans that would not show up on the books thereby concealing the real size of Greece’s debt load. To cover is ass, Goldman then shorted those bets and in 2009 joined with other Wall Street predators in a concerted move against the Euro further exacerbating the Greek financial crisis. Predictably, these bets didn’t go so well for the Greeks.

Goldman Sachs, the infamously-branded Vampire Squid – an appellation courtesy of Rolling Stone’s Matt Taibbi – even levied a thinly-veiled threat to the Greek Parliament earlier that year, demanding it appoint a pro-austerity prime minister or risk having central bank (ECB) liquidity cut off to their banks.

In an interview with Der Spiegel early in 2015, then newly-elected Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras is quoted as saying that the European Central Bank (ECB), the bank that manages the EU money supply, was “holding a noose around Greece’s neck.” Ellen Brown in a March 2015 post on Web of Debt explains:

The noose around Greece’s neck is this: the ECB will not accept Greek bonds as collateral for the central bank liquidity all banks need, until the new Syriza government accepts the very stringent austerity program imposed by the troika (the EU Commission, ECB and IMF).

That means selling off public assets (including ports, airports, electric and petroleum companies), slashing salaries and pensions, drastically increasing taxes and dismantling social services, while creating special funds to save the banking system.

These are the mafia-like extortion tactics by which entire economies are yoked into paying off debts to foreign banks – debts that must be paid with the labor, assets and patrimony of people who had nothing to do with incurring them.

And this is not limited to just Greece. All banks are dependent on the liquidity provided by central banks because they all leverage debt and lend money that they don’t have. The central bank is the “lender of last resort” providing the fiat currency and credit to keep them in business. Central banks have the power to control the currency and as such the economy.

But with respect to Greece, as with other real-world examples we will offer, there is a kicker. All of that public debt — leveraged by bonds, Credit Default Swaps, interest rate swaps, currency swaps, and other exotic financial instruments — were bought, funded by loans from a central bank, by its private banking customers who after all are members in The Club who get bailed out by the central bank if their bets don’t pan out. How does this work? Ellen Brown continues:

Essentially, Greece’s public debt went from private to public hands when the ECB and the IMF rescued private (German, French, Spanish) banks. The debt, of course, ballooned. The troika (ECB, IMF, and the EU) intervened, not to save Greece, but to save private banking. The ECB bought public debt from private banks for a fortune, because the ECB could not buy public debt directly from the Greek state. The icing on this layer cake is that private banks had found the cash to buy Greece’s public debt exactly from…..the ECB, profiting from ultra-friendly interest rates. This is outright theft. And it’s the thieves that have been setting the rules of the game all along.

So who gets left with the tab? Get out your wallets again citizens.

The primary takeaway from this discussion so far, aside from the fact that the potential events in our example actually played out albeit with vastly greater consequences, is that the process of creating money under just such a privately-owned and run banking system allows an influential few who have it, to control the destiny of the many who have been made to believe that they need it in order to spend it so they can become model citizens.

What is often lost in the fine print is the fact that all of this money is created literally out of thin air and carries with it a vastly greater burden of leveraged debt – the original principal plus the interest plus wagers on the future performance of the original debts – owed to whomever holds the debt contracts – which is usually the insider clients of the private banking entity that creates the debt and controls the money supply. The operative word here is control. How much are we talking about? Estimates including reports from the Bank for International Settlements, dating as far back as 2008 put the total “notional” value of outstanding derivatives — potential face value of debt from bets – at $1.2 Quadrillion. Yes, that’s a “Q”.

THE POWER OF CENTRAL BANKS

The Bank For International Settlements (BIS).

Let’s get back to the power wielded buy the Central Banks, specifically the Bank For International Settlements. Most people have never even heard of it. Dr. Carroll Quigley – a professor of history at Georgetown University and mentor to President Bill Clinton wrote in Tragedy and Hope: A History of the World in Our Time (1966):

“[T]he powers of financial capitalism had another far-reaching aim, nothing less than to create a world system of financial control in private hands able to dominate the political system of each country and the economy of the world as a whole. This system was to be controlled in a feudalist fashion by the central banks of the world acting in concert, by secret agreements arrived at in frequent private meetings and conferences. The apex of the system was to be the Bank for International Settlements in Basel, Switzerland, a private bank owned and controlled by the world’s central banks which were themselves private corporations.”

To Professor Quigley the key to success for this exclusive banker’s club would be that both the political and economic systems of its member countries would be controlled by a network of bankers and not by the citizens of those countries. In fact there were two basic tenets or rules of order for governing the internal strategies at the BIS – the first being that banks should act independently from their governments and, second that politicians must not be allowed to dictate policy for the international monetary system. Initially the BIS kept a low profile, operating out of an abandoned hotel, the Grand et Savoy Hotel Universe, with an annex above a chocolate shop. But in 1977 it moved to an eighteen storey circular tower replete with its own nuclear fall-out shelter, dubbed by pundits as the Tower of Basel.

Founded in 1930, the BIS was to function as a depository for Germany’s war reparations payments mandated by the Treaty of Versailles but its real purpose was to become an international clearinghouse for central banks — the first in the history of the world. The bank’s key architects were Montagu Norman, who was then the governor of the Bank of England, and Hjalmar Schacht, then the president of the Reichsbank.

In his book Tower of Basel: The Shadowy History of the Secret Bank that Runs the World, author Adam LeBor states the case that during WW II “the BIS became a de-facto arm of the Reichsbank, accepting looted Nazi gold and carrying out foreign exchange deals for Nazi Germany” even though at the time its president was an American, Thomas McKittrick and its General Manager a Frenchman Roger Auboin.

In his book Tower of Basel: The Shadowy History of the Secret Bank that Runs the World, author Adam LeBor states the case that during WW II “the BIS became a de-facto arm of the Reichsbank, accepting looted Nazi gold and carrying out foreign exchange deals for Nazi Germany” even though at the time its president was an American, Thomas McKittrick and its General Manager a Frenchman Roger Auboin.

A few miles away, Nazi and Allied soldiers were fighting and dying. None of that mattered at the BIS. Board meetings were suspended, but relations between the BIS staff of the belligerent nations remained cordial, professional, and productive. Nationalities were irrelevant. The overriding loyalty was to international finance.

— Excerpt from LeBor, Adam (2013-05-28). Tower of Basel: The Shadowy History of the Secret Bank that Runs the World.

As Ellen Brown points out in her book The Public Bank Solution: From Austerity to Prosperity:

The BIS has been called “the most exclusive, secretive, and powerful supranational club in the world.” Its purpose was to allow bankers to make money no matter what, and to continue exercising their vast powers, including making agreements on “the economic future of the chief areas of the globe.” Today the BIS has governmental immunity, pays no taxes, and has its own private police force. It is, as its founders envisioned, above the law.

The Federal Reserve.

The central bank here in U.S. is the Federal Reserve. It is a hybrid institution, a publicly run, yet for the most part privately-owned banking system. It was created in 1913 when then U.S. president Woodrow Wilson signed into law The Federal Reserve Act. The seven bankers that sit on its Board of Governors together with its Chairperson are appointed by the President of the United States and approved by the US Senate. The directors of its twelve regional branches are elected by nationally-chartered member commercial banks from their respective districts, whom are required to hold stock in the Fed.

In practice, all members of both the the Fed’s Board Governors and its regional branch boards are bankers, most of whom are Wall Street insiders who’ve either worked at or will work at the large commercial investment banks such as Goldman Sachs or JP Morgan Chase. The money supply for the US, although it is ostensibly controlled by the Treasury Department whose Treasury Secretary has historically been a Wall Street insider, effective control is managed through the Federal Reserve. The stated reason for this public-private duality goes as follows:

The Federal Reserve is theoretically free from political pressure and considers itself an independent central bank because its monetary policy decisions do not have to be approved by the President or anyone else in the executive or legislative branches of government, it does not receive funding appropriated by the Congress, and the terms of the members of the Board of Governors span multiple presidential and congressional terms. — Wiki.

The Federal Reserve, like all central banks makes a lot of money because it controls the money supply. The majority of its revenue comes from open market operations—specifically the interest on the its own portfolio of Treasury securities as well as the money that comes from the buying and selling of the securities in its portfolio and their underlying derivatives. So the Fed is also making bets using taxpayer money. Some critics view private-banker control over the creation the money supply to be a scam. But it has been a profitable relationship for the Treasury. In 2014, the Fed sent $98.7 billion of its $101.5 billion total net income to the U.S. Treasury.

Other Fed revenue comes from the sale of financial services like check and electronic payment processing and discounts (fees) on loans to member banks. There also is interest and fees on foreign deposits held within the Federal banking system. However, the Fed doesn’t really keep the profits. The Fed transfers all profits to the Treasury after deducting a 6% dividend for its member banks and certain expenses.

Fiscal Policy

It is evident then that Central banks, after taking their cut, make a lot of money for their governments that ostensibly can be used for running public programs like administrative agencies, healthcare, education, transportation, social services, and defense. When combined with revenues received from taxes, borrowing, or the sale of assets, this income stream is the life blood of publicly-run institutions and greatly affects their role in the local and national economy. The control and management of this income stream is called Fiscal Policy and its tools – implemented and administered politically via the executive and legislative processes – are the levying of taxes, setting tax rates, the collection of fees for licenses and public services, and borrowing for civic improvements or operations funded via bond issues. And much like Monetary Policy that is exercised by the Fed, Fiscal Policy is very sensitive to interest rates. How senstive?

Libor

Remember the LIBOR scandals that have rocked the financial industry in Europe and implicated HSBC, JP Morgan Chase, RBS, Barclays, CitiGroup, Bank of America, and others? So what is LIBOR? It is an acronym standing for London Interbank Offer Rate, an interest benchmark based on the rates at which banks lend unsecured funds to each other on the London interbank market, and is published daily by the British Bankers’ Association (BBA).

Each morning, global banks submit their (estimated) borrowing costs to the Thomson Reuters data collection service. The calculation agent throws out the highest and lowest 25 percent of submissions and then averages the remaining rates to determine Libor. Calculated for fifteen different maturities and ten different currencies, Libor is considered the most critical global benchmark for short-term interest rates. Eighteen banks submit rates for the U.S. dollar LIBOR.

Many banks worldwide use Libor as a base rate for setting interest rates on consumer and corporate loans. Indeed, hundreds of trillions of dollars in securities and loans are linked to Libor, including auto and home loans, according to the U.S. Commodities Futures Trading Commission. When Libor rises, rates and payments on loans often increase; likewise, they fall when Libor goes down. Some 45 percent of adjustable-rate prime mortgages and 80 percent of adjustable-rate subprime mortgages are based on Libor, while half of variable-rate private student loans are set to Libor. —- Council On Foreign Relations.

Crikey! What’s the big deal here anyway? How does monkeying with interbank interest rates affect you and me? Well, LIBOR is used as a benchmark to set payments on those $1.2 quadrillion of notional financial instruments, ranging from complex interest-rate derivatives to simple mortgages. The number determines the global flow of trillions of dollars each year and you have to wonder what role the BIS has in setting these LIBOR rates.

Because LIBOR is used in US derivatives markets, an attempt to manipulate Libor is an attempt to manipulate US derivatives markets, and thus a violation of American law. Since mortgages, student loans, financial derivatives, bond issues, and other financial products often rely on Libor as a reference rate, the manipulation of submissions used to calculate those rates can have significant negative effects on consumers and financial markets worldwide.

The inescapable conclusion here is that we have a worldwide banking system that for a period of time, manipulated inter bank interest rates at will in order to stiff the borrower – the consumer – and pocket the profits as capital gains. If you as as a broker under such a scheme could shave off even one thousandth of a point (.001%) from the lending rate on such a sum and pocket the difference it would amount to $12 billion!

Flash Trading

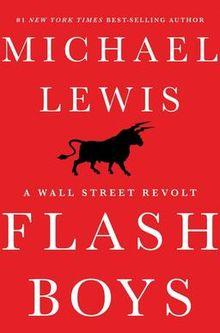

Then there is Flash Trading better known as High Frequency Trading (HFT). In his book Flash Boys, Michael Lewis exposed the dangers of high-frequency trading in the equities markets where traders front-run securities trades using state-of-the-art technologies like fiber optic cable and microwave transmission systems to shave milliseconds off of the time it takes to complete a transaction on the stock market.

Many such HFTs are the result of using electronic platforms for entering trading orders with an algorithm which executes pre-programmed trading instructions accounting for a variety of variables such as timing, price, and volume. Algorithmic trading, thought to be a contributing factor in the Flash Crash of May 2010, is widely used by investment banks, pension funds, mutual funds, and other buy-side (investor-driven) institutional traders, to move large securities trades, dividing them into several smaller trades to ease their relative market impact and and to manage risk. While Lewis can only estimate the cost to investors of the abuses, he believes it is over $5 billion per year, perhaps as much as $15 billion per year or even higher.

Dark Pools

There are also securities trading forums called Dark Pools. Dark pools are run by private brokerages which operate under fewer regulatory and public disclosure requirements than public exchanges. The bulk of dark pool trades represent large trades by financial institutions that are offered away from public exchanges like the New York Stock Exchange and the NASDAQ, so that such trades remain confidential and outside the purview of the general investing public. The fragmentation of financial trading venues and electronic trading has allowed dark pools to be created, and they are normally accessed via private contractual arrangements.

Caveat Emptor

What the existence of the above unregulated financial market exchanges, both those visible and those more opaque, illustrate is the almost limitless power these institutions have over the global economy, having the potential to bring down governments and dictate the future of entire economic ecosystems because such systems are being and have been used to move large volumes of debt from market to market largely out of the purview of regulatory agencies for stupendous profits.

Remember, debt carries with it a demand to be repaid, wielded by central banks like a bludgeon in their campaigns of economic class warfare. Why, besides for the money? Because these neoliberal money factories have bought and sold governments and entire countries for decades. Historically we can cite some famous examples: Cuba in the 1960’s; the southern cone of South America in the 1970’s; Russia and Poland in the 1980’s; Iraq; Iceland; Spain; and currently Venezuela, Syria, Greece, and Ukraine.

But more to our point, central banks also aggressively market and fund this Forever War in order to perpetuate a climate of fear. They work doggedly, most often in secret to keep the populations at large marginalized; unemployed, poor, hungry, disorganized and imprisoned by debt. Banksters and the elites they work for are not interested in democracy. They are interested in privacy. Membership to the Club is restricted. They do not want to live in a world where everyone has a equal voice. That would constitute a threat to the invisible hand of the Free Market. Remember Occupy?

If you are not a member of the Club, you can’t complain about the service. The only freedom neoliberal economics offers non-members is the freedom to choose when to buy. Through their Chicago-school Free Market dogma, neoliberal capitalists have purposely hyperextended the global economy to the tune of $1.2 Quadrillion by gambling with OPM; other people’s money.

So the operative question, given our already empty wallets, is not if but when will we be given the freedom to pick up the tab?

© Kazkar Babiy MMXIV.

Be sure to read Chapter One, Chapter Three and Chapter Four of The Neoliberal Book of the Dead. Just follow the links provided.