Stephanie Kelton — 18 September 2022

When I wrote this column for the New York Times in early April 2021, I encouraged the Biden administration to think differently about how to respond to any unexpected pop in inflation. Inflation wasn’t a raging problem at the time, but some economists were starting to muse about the possibility of a breakout in prices. In the same month that my article appeared, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reported that consumer prices had risen at an annual rate of 2.6% in March. The following month, they confirmed that inflation had accelerated at its fastest pace in more than 12 years, jumping to a year-over-year rate of 4.2% in April. We had an emerging problem on our hands.

My piece was full of ideas about how to tackle a potential—but not yet real—inflation problem. I wrote about supply bottlenecks, immigration and trade policies, taxes, lowering health care costs, building manufacturing capacity, and more. I described a whole suite of inflation-dampening policies, many of which were later embraced by the administration and by some of the economists who initially dismissed my piece on the grounds that mainstream economics tells us that any inflation threat can easily be contained by monetary policy. I explained in this thread why I disagreed with that view.

And while some mainstream economists now agree that broadening the inflation-fighting toolkit is a good idea, they still insist that indiscriminate interest rate hikes are the weapon of choice and that the Federal Reserve must go long and hard in order to slay the inflation dragon.

Here’s former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers, commenting on where he thinks the Fed needs to take interest rates now that the August inflation data appears to have taken a more modest path for future rate hikes off the table:

Gradualism and tentativeness are not the best approach. We must be firm and resolute.

My feeling is they’re going to have raise rates more. I think it would help if the Fed were more realistic and honest.

Even as the prospect of more aggressive Fed tightening raised expectations of a more severe economic slowdown and threw financial markets into turmoil, Summers made the rounds to deliver this reassuring message.

As always, one must read Summers’ public declarations with care. He is always careful to leave himself with an exit, should the need for backpedalling arise. He does it here by attaching carefully-chosen adjectives: “…MAJOR example…EXCESSIVE speed…LARGE cost…” He’s attempting to rule out any historical example of a policy-induced calamity by rhetorical design.

Summers (and others) want us to understand the current bout of high inflation as evidence that policymakers overstimulated the macro economy, causing it to “overheat.” To bring inflation back down, he (and others) insist that interest rates and unemployment need to move much higher.

For more than a year now, Larry has flogged the Fed for being too slow to remove the punch bowl. Now that they’ve “fallen behind the curve,” Summers insists that Powell & Co. must make up for lost time by jacking interest rates—and unemployment—way up.

Sound scary? Not to Larry. Remember, there are no major examples where the central bank forced a large cost onto the society by reacting with excessive speed to bring down inflation.

What Is the Possible Impact of Fed Rate Hikes?

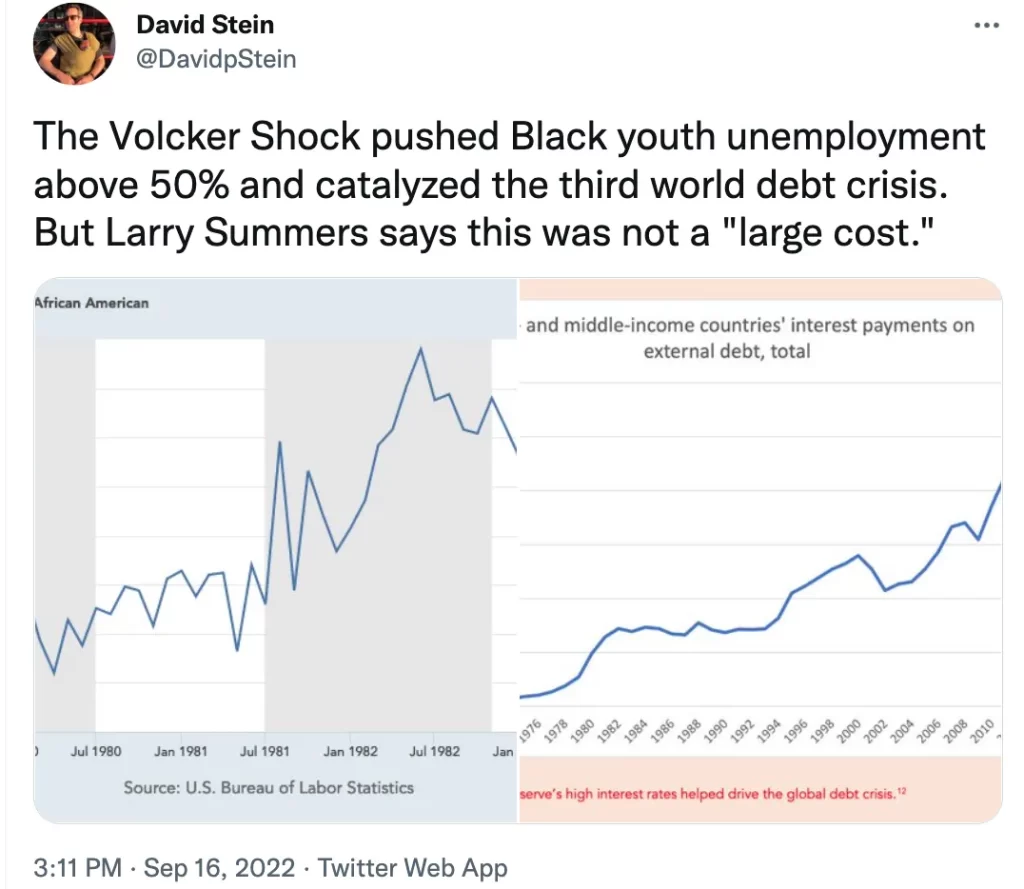

Plenty of people, including this history professor from UC Santa Barbara, immediately countered Summers, reminding us that rate hikes have indeed caused immense suffering.

For more on the history of policy-induced calamities, I suggest reading this Public Policy Brief by MMT economists Yeva Nersisyan and L. Randall Wray. Here are some excerpts:

[T]he Fed has never managed to guide the economy to a soft landing with rate hikes. Many point to Fed Chairman Paul Volcker’s interest rate hikes in the 1970s—to 20 percent and beyond (and above 15 percent for a couple of years)—as an example of using monetary policy to quell inflation. But the economy crashed into deep recession, and a series of financial crises (the thrift crisis of the early 1980s, the developing country debt crisis later in the 1980s, and the big bank crisis at the end of the 1980s) can all be traced to Volcker’s experiment. Chairman Greenspan’s tightening in the early 1990s brought on a recession followed by our first jobless recovery, and his tightening in 2004 helped to bring on the global financial crisis and another, even longer, jobless recovery….

Realistically, the only way in which monetary policy can affect inflation is by significantly slowing down the economy and raising unemployment sufficiently to alleviate wage pressures—which, as we have argued, are not now driving inflation, but are simply trying to catch up to price increases. Small rate hikes do not reduce inflation; it takes large rate hikes that create financial crises, insolvency, and bankruptcies severe enough to crash the economy—followed by jobless recoveries. In other words, the Fed would be using unemployment as a tool to control the rate of inflation. Killing the recovery also means reversing the progress made recently on raising incomes at the bottom…

It is difficult to foresee how financial markets might react to another recession in conjunction with rising interest rates. We know that the financial sector has become accustomed to 15 years of unprecedentedly low borrowing costs. Will it unravel when faced with negative GDP growth and substantially higher interest rates?

The appropriate solution to inflation would be to work to alleviate supply-side constraints. That, however, cannot really be achieved by monetary policy. In fact, cutting interest-sensitive spending, such as investment, would work to constrain our capacity to produce (i.e., supply) in the future. The pandemic has taught us that the United States must become less reliant on foreign production, and we need massive investments in alternative energy projects to free us from the grip of OPEC-Plus, which includes Russian oil production. We need more domestic investment, not less.

The Fed seems to be embarking on a dangerous experiment.

One might even say that going “full Larry” gives us approximately a 3 in 3 chance of a very bad outcome with large costs that will be borne disproportionately by those who can least afford to bear them.

First published on The Lens.