Everyone who has followed my writings through the years knows I like to write specific arguments for the idea of unconditional basic income (UBI). One of my own personal favorites is the Engineering Argument for UBI. Another is the Monsters, Inc Argument for UBI. Well, here’s another that’s been on my mind since around 2016 that I’ve only ever mentioned here and there without ever writing a full essay diving into it. This is my attempt to finally get it out there. Let’s talk about the Big Red Button that could mean the extinction of humankind, and how implementing UBI will actually help us avoid pressing it.

The Big Red Button

Imagine there’s a device with a Big Red Button. If someone pushes that button, it means the extinction of our species. All humans will die if one human presses that button. How do we avoid that button getting pressed?

The most obvious response is to never make that device. But we’re humans. We’re going to make that device. That device is absolutely getting made. So the next most obvious response is to make that button really really hard for anyone to press. There needs to be as few of these devices as possible. There needs to be all kinds of walls and barriers erected to make pressing that button more difficult, both physical and legal. It needs to be a crime to gather the materials for the device, and there needs to be all kinds of flags that are triggered to signal that someone is attempting to press the button. This is the strategy we’ve taken for nuclear weapons. It’s extremely difficult for a country to get its hands on nuclear weapons, and it’s virtually impossible for any lone person to make one themselves.

Here’s the thing though, the nuclear button isn’t the Big Red Button we should all be worried about. The Big Red Button we should all be worried about isn’t even really the creation of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in the form of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) that’s smarter than us. Yes, there’s great risk inherent in super intelligent AI, but that risk is not akin to lots of people getting a button to potentially push, but instead a button pushing itself without human input. Extreme climate change is also a danger with existential risk, and we certainly need to reverse it before it’s too late, but we pushed that button long ago, and there is the potential we can potentially unpush it with smart policies and new technological advancements in direct air capture (DAC). There’s still hope.

The Big Red Button I want to talk about is biotechnology, because once someone pushes that button, there is potentially no going back. To help in understanding why I think that is, let’s first talk about lawn mowers.

Automation Versus Obsoletion

I used to mow lawns for money as a kid. I had a very small customer base of people in my community. They were all within walking distance. I remember as a kid drawing up plans for a robotic lawn mower. How cool would that be to just sit back and watch a robot mow a lawn so I didn’t have to do it? Especially my own lawn. My sketch involved setting up a border around the lawn so that the robot would know where to go and where not to go. It seemed so obvious a device to make. At the time, I just thought it would be awesome. It wasn’t until much later as an adult, I started thinking about the employment implications of automating the job.

If there are robots that can mow lawns, that will put lawn mowers out of work. A company that used to employ a team of 50 lawn mowers could downsize and still mow as many lawns, or it could mow a lot more lawns and take business away from other lawn mowers. Either way, in a world with robotic self-driving lawn mowing technology, there’s going to be fewer jobs mowing lawns.

That’s automation. It’s powerful. It can do a lot of work for us. That technology also already exists by the way. First there were Roombas vacuuming floors for us. Now there are lists of the best robot lawn mowers. They’re here. They exist. And they’re already reducing demand for human lawn mowers.

However, what if we didn’t even need robot lawn mowers anymore? One way to do that is to just not have lawns anymore. Another is to have fake lawns. Some people would love either, and both would certainly save a lot of water, but as long as there’s a demand for real lawns, there’s going to need to be mowers. Except, that’s not entirely true. It’s theoretically possible to genetically engineer some grass that wouldn’t need cutting. Now imagine the implications of that. It’s one thing to automate something. It’s another to completely obviate the need to automate.

With human lawn mowers, let’s say a town needs to employ 1,000 lawn mowers. With robot lawn mowers, let’s say a town needs to employ 100 lawn mowers. With biotech super grass, that town and every other town would need zero lawn mowers. And one biotech company employing a tiny fraction of the number of people once employed mowing lawns could gain a massive amount of revenue and concentrate it into the hands of very few very rich people. That’s the power of biotech compared to robotics.

Now here’s another story that goes far beyond super grass. One of my favorite sci-fi books I’ve ever read is The Diamond Age by Neal Stephenson. I don’t want to spoil the book, but it takes place in a future where nanotechnology exists. People’s homes have a kind of replicator called a Matter Compiler that’s connected to a kind of plumbing system. Instead of just having water on tap, people have virtually everything on tap. It’s important to understand there are limits due to the centralized nature of the system. At the push of a button, voila, there’s a new shirt, but you can’t make a bomb. Sounds like Star Trek, right? Well, the key technology in the book that’s the next advance is Seed technology, which is the ability for anyone to grow anything from special nanotech seeds. And I mean anything. No limits. Someone could choose to grow a pandemic virus to wipe out humanity. They could even just program nanobots to self-replicate until there’s nothing but nanobots. Sci-fi fans knows this as a Gray goo scenario. That’s a Big Red Button.

It really got me thinking when I first read that. How does humanity survive if we create technology that can create anything at all? That’s what I love about science fiction. It really gets us thinking and imagining and wondering. Part of being a science fiction fan is contemplating problems before they exist, and finding potential solutions to those problems before they are needed.

What we really need to understand now is that those science fiction problems are a lot closer than many people think. AI has already arrived, and AI is already on its way to enabling someone somewhere to push the Big Red Button.

Building the Big Red Button

One of the first revolutionary accomplishments by AI has been a massive step toward solving the protein folding problem. A decades-long problem in biology has been not knowing what shapes proteins would take and the time and resources required to try and predict them with any accuracy. Then DeepMind’s AlphaFold (and more recently AlphaFold2) changed all of that with its ability to better predict the shapes of virtually every protein. This quickly grew the database of known protein structures from a few hundred thousand to hundreds of millions and has already led to new advances including new antibiotics and improving the ability to edit genes. The world’s first fully AI-generated drug is also already in clinical trials.

Next, have you heard of ChemCrow? Most of you probably haven’t. A few of you trying to follow AI developments have. In April 2023, a paper was published describing “an LLM chemistry agent designed to accomplish tasks across organic synthesis, drug discovery, and materials design.” The AI researchers developed an AI that “autonomously planned the syntheses of an insect repellent, three organo-catalysts, as well as other relevant molecules.” Basically they created an AI attached to a chemistry lab that synthesized new compounds via a simple chatbot interface. They stated the obvious in their paper that “there is a significant risk of misuse of tools like ChemCrow.” On the one hand, chemists using AI could potentially make more incredible discoveries faster, and non-experts could be empowered to help too. Those are astounding implications for scientific advancement. On the other hand, such tools can better enable people to make things none of us want made, on purpose or by accident.

That was in April. This next paper was published in June 2023. The following is directly from the abstract, and I want to emphasize this is real, not sci-fi:

“MIT tasked non-scientist students with investigating whether LLM chatbots could be prompted to assist non-experts in causing a pandemic. In one hour, the chatbots suggested four potential pandemic pathogens, explained how they can be generated from synthetic DNA using reverse genetics, supplied the names of DNA synthesis companies unlikely to screen orders, identified detailed protocols and how to troubleshoot them, and recommended that anyone lacking the skills to perform reverse genetics engage a core facility or contract research organization. Collectively, these results suggest that LLMs will make pandemic-class agents widely accessible as soon as they are credibly identified, even to people with little or no laboratory training.”

That’s the Big Red Button. No need for AGI. No need for any kind of Skynet to come online and decide to nuke humanity. All that’s needed is the right LLM connected to the right tools, and a lone human willing to send the commands.

If you think AI tools like ChatGPT and Bard from the big guys at OpenAI and Google can put limits in place to prevent such uses, you’re probably right. But that’s not the real danger. The real danger is open source AI where a single person has the ability to train their own unrestricted AI, and that’s something the big guys already fear too.

There Is No Moat

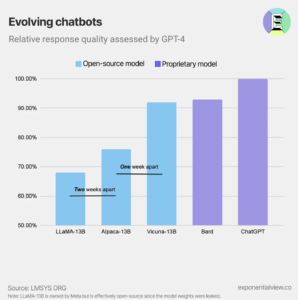

A leaked internal Google document in May 2023 stressed the dangers to Google that open source AI poses, and how the open source community was positioned to out-compete both OpenAI and Google. It all started when Meta’s foundational model was leaked. Within weeks, there were open source advancements made with it bringing open source options up to the level of Google’s Bard and OpenAI’s ChatGPT. Advancements were made at a shocking pace, making it possible to run powerful AI models on a phone versus a giant array of servers, and bringing people the ability to train their own AIs in one day for their own custom needs.

Whereas Google and Microsoft were putting massive resources and massive training time behind massive models, the open source community was iterating better and better AI models, cheaply and quickly, based on the volunteer work of thousands upon thousands of people around the world, one improvement at a time. It seems clear already that whatever AI technology is invented with protections and guardrails in place, there will be open source AI options of similar capability without the protections in place too. People who know what they are doing will likely be able to use AI for what they want, regardless of what the rest of society wants to prevent AI from doing.

“The more tightly we control our models, the more attractive we make open alternatives. Google and OpenAI have both gravitated defensively toward release patterns that allow them to retain tight control over how their models are used. But this control is a fiction. Anyone seeking to use LLMs for unsanctioned purposes can simply take their pick of the freely available models.”

So if open source AI is going to be a Big Red Button, how do we reduce the odds of someone pressing it by training their own regardless of any regulations and laws designed to try to prevent that? If anyone can build a new pandemic virus with AI, what do we do? The answer is simple, but achieving it will not be.

The answer is we have to build a society full of people less likely to ever want to push the button.

That may not be a satisfying answer. It certainly isn’t considered satisfying when it comes to the problem of mass shootings in America, but it’s ultimately the answer to that too. We can try to keep guns out of the hands of people who want to use them to kill a bunch of people, but that becomes harder and harder to do when someone can just print a gun in their house. Ultimately, there’s nothing else to do but get at the roots of the real problem. What makes someone want to kill a bunch of people? If it’s a mental health issue, then what improves mental health? If it’s a social erosion issue or inequality issue, then what improves social cohesion and reduces inequality? What’s the root problem so we can solve it?

How to Create Big Red Button Pushers

In 1999, Ichiro Kawachi at the Harvard School of Public Health led a study investigating the factors in American homicide. He measured social capital (interpersonal trust that promotes cooperation between citizens for mutual benefit), along with measures of poverty and relative income inequality, unemployment, education, alcohol use, homicide rates, and the incidences of other crimes like rape, robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, larceny, and motor vehicle theft. He was then able to identify which variables were most associated with which particular types of crime.

What he found was summarized in The Joker’s Wild: On the Ecology of Gun Violence in America, which I also recommend reading.

“When income inequality was higher, so was the rate of homicide. Income inequality alone explained 74% of the variance in murder rates and half of the aggravated assaults. However, social capital had an even stronger association and, by itself, accounted for 82% of homicides and 61% of assaults. Other factors such as unemployment, poverty, or number of high school graduates were only weakly associated and alcohol consumption had no connection to violent crime at all… The clear implication is that social capital followed by income inequality are the primary factors that influence the rate of homicidal aggression.”

In a follow-up study Kawachi also found that when social capital in a community declined, gun ownership rates increased. This is a correlational finding, but a reasonable interpretation is that people who come to trust other people less are more likely to look to guns to provide a greater feeling of security. So although there may be good reason to reduce the availability of AR-15s to reduce the number of kills per mass shooting, so long as guns are in a highly unequal society with heavily eroded social capital, where people feel they’re on their own in life and surrounded by people they don’t trust, there will likely continue to be mass shootings.

The problem is how much easier it has become to see “them” instead of “us” and the resulting fall of trust in others. Massive inequality tears at the bonds of community. Instead of all being in this together, surrounded by neighbors we consider friends regardless of disagreements, we see the world as being full of people we no longer even see as human. Living insecure lives full of a feeling of isolation is terrible for our collective mental health and leads directly to violence.

So if social capital is what we need to regrow, and that is defined as interpersonal trust that promotes cooperation, how do we do that? Well, that’s where unconditional basic income comes in. Far beyond just being money to reduce poverty, which again is not well-correlated with violent behavior, UBI is literally an act of interpersonal trust. It is a community deciding that everyone in the community should be trusted with money, which is itself a tool of trust. Basic income is an act of trust, first and foremost. With that trust comes a real sense of security. If everyone is unconditionally trusted with the same amount of resources as everyone else in the community, insecurity falls, as does inequality. The universality and equality of UBI are also both unifying. Stress is relieved. People breathe more freely, and that breath is full of gratitude for the entire community.

Creating Fewer Big Red Button Pushers

In the Finland basic income experiment, most people tend to focus on how it didn’t reduce employment and in fact slightly increased employment, but what I personally found to be the most incredible finding was how trust increased. Participants in the pilot who received unconditional basic income expressed higher levels of trust in their own future, their fellow citizens, and public institutions. It also reduced their stress levels and improved their mental health. It reduced loneliness. Finland’s pilot demonstrated that UBI is far more than money. It is social capital.

Another important observation was made thanks to a permanent UBI that started being provided in North Carolina to members of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians in 1996. A study of children growing up in poverty was already ongoing when it started, so it has been a goldmine for researchers ever since. Remarkably, the UBI increased agreeableness of the kids in families who received it. They grew up to be more comfortable around other people and better at teamwork. They had fewer behavioral and emotional disorders. As adults at age 25 and 30, the kids who grew up with UBI had a third of the anxiety and half the rates of depression of the kids who grew up without UBI. They have had fewer illegal behaviors.

Crime consistently falls in basic income pilots that utilize saturation sites where regular income is received universally, community-wide. In the Dauphin pilot in Canada in the 1970s where an entire town received a guaranteed basic income every month for about five years, overall crime fell by 15% and violent crime fell by 37%compared to similar towns that did not receive the income security. Mental health also improved so much that hospitalizations fell by 9%. In the Namibia UBI pilot, overall crime dropped by 42% and in Kenya domestic violence dropped 51%.

UBI pilots have also shown increased social cohesion. In Namibia, researchers observed that “a stronger community spirit developed.” In India’s UBI pilot, researchers observed that traditionally separate castes began to work together, which was especially surprising given the long history of India’s caste system. As one researcher described it, “The castes don’t normally ‘come together’, but the women of different castes in the villages did come together.” In a natural UBI experiment in Lebanon, the UBI led to people being 19% more likely to provide help to other members of their community. Members in the UBI community even reported receiving fewer insults from other members of the community.

A huge study of the impact of unconditional monthly cash transfers, covering twelve years and 100 million people, found that income security reduced suicide risk by 61%. Considering how many mass shootings are intended as a final act, I think it’s important to keep this in mind too when it comes to the Big Red Button. Pushing the button isn’t only about wanting to kill other people. It can also be about killing one’s self and deciding that if other people die too, that’s fine because nothing matters anymore anyway.

Unconditional cash has even been tested against therapy, and it was significantly more effective at improving mental health than the therapy that cost almost three times as much. Over and over again, this kind of finding has been replicated. A systematic review of decades of studies has shown that policies that improve social security benefit eligibility/generosity are associated with improvements in mental health while social security policies that reduce eligibility/generosity are related to worse mental health. Unconditional income improves mental health. We know that unequivocally. The Canadian Mental Health Association has even already officially endorsed UBI for that reason, as has the Canadian Medical Association.

Conclusion

Is UBI going to solve everything? Will it eliminate all mental health issues, end all crime and violent behavior, stop all suicides, and prevent all mass shootings? No. It’s not a cure-all. But it is a help-most-everything. It will improve mental health, reduce crime and violent behavior, reduce suicides, and reduce mass shootings because it increases social capital and economic security, and decreases inequality. UBI will help a lot of things all at once in a significant way, which brings me back to the Big Red Button.

Unconditional basic income will not reduce the probability of someone pushing the Big Red Button down to zero percent. But, we’re talking about existential risk. If we did a randomized control trial experiment where 100 civilizations were provided Big Red Button machines and half of them had UBI and half of them didn’t, and the result was that significantly fewer civilizations with UBI pushed the button, then clearly UBI is a smart thing to do and a very dumb thing not to do.

The Big Red Button Argument for UBI is that if we’re going to make a Big Red Button that can cause humanity’s extinction if pressed, and we know UBI will reduce the odds of someone pushing that button, then for the sake of all human civilization, implement UBI immediately. Before it’s too late.

First published on UBI Guide.

Shared via Creative Commons.

![]()